In case you’ve been living under a rock for the past week, let me catch you up on some fairly significant world events:

- On June 23, British voters opted to leave the EU.

- The British Pound plunged to a 30-year low (and it’s still falling).

- $4 trillion have been erased from global equity markets.

- David Cameron announced he’s stepping down as Prime Minister.

- Britons are applying for Irish passports en masse.

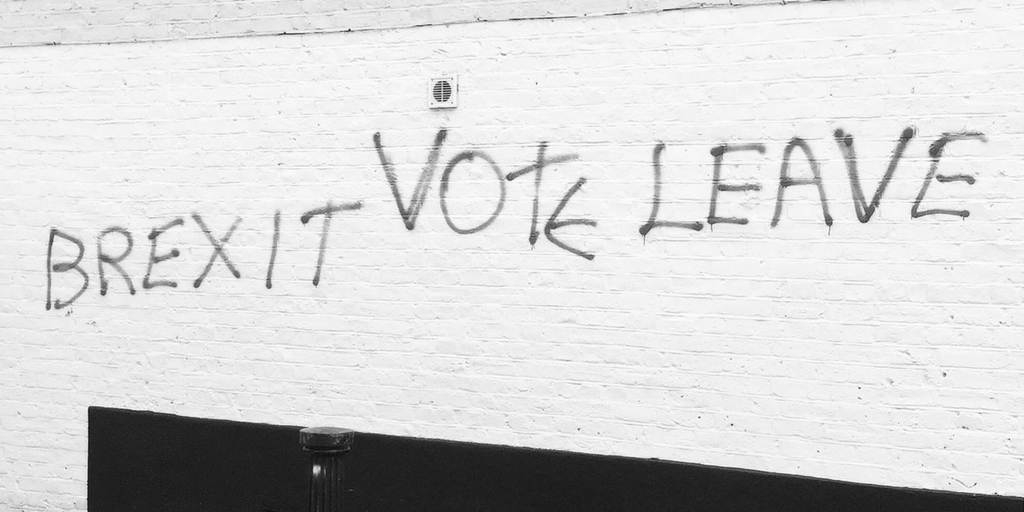

In short, this whole Brexit thing is a pretty big deal. Not only because of the worrying economic effects it could have on Britain, Europe and the rest of the world… but also because no one really saw this coming.

The politicians, the financial markets, and the talking heads on television pretty much all agreed there was no way Britons would vote to leave the European Union.

Until they did.

So how exactly did this happen?

In an interview with Harvard Business Review, Steve Martin — persuasion science expert at Influence at Work UK — pinpoints how the “Remain” campaign lost the battle of persuasion to the “Leave” campaign.

#1 – Focus on one core message.

There seems to have been a focusing effect. The Leave side made sure that immigration became a focus. Not only a focus but the focus. And once that’s a focus it’s hard to get other messages through. — Steve Martin

It’s not hard to see how the Remain campaign failed to resonate when compared to the simplicity of the Leave campaign.

Leave: “Those immigrants are taking our jobs. Leave the EU. Kick out immigrants.”

Remain: “Leaving the EU would have catastrophic effects to the British economy. Our currency would crash. And we’d threaten relationships with our largest trading partners.”

Remain’s message is clearly the more intelligent argument.

But the simplicity of Leave’s message speaks directly to the gut, which is where most decisions are ultimately made.

#2 – Warn against immediate danger.

Research shows us that we’re kind of present-orientated beings. So trying to use a complex economic argument that is full of data and has the word prediction or forecast in it is difficult. That kind of argument possesses uncertainty-raising qualities rather than certainty-raising qualities. — Steve Martin

Sure, bad things could happen if Britain leaves the EU. But could isn’t very compelling.

On the flip side, there’s an immigrant in my office who’s directly competing with me for that promotion.

He’s much more dangerous to me than what could happen to the British economy.

#3 – Don’t try too hard.

When people become conscious you’re trying to persuade them, that can raise resistance, and resistance is a killer when it comes to persuasion. It creates a mental barrier that will stonewall and kill an idea. — Steve Martin

No one likes being sold to.

You don’t like it when a sales person is desperately trying to persuade you to buy whatever they’re selling. And your buyers don’t like it when you try to peddle your latest service offering without considering what they actually need.

British voters didn’t like being sold to either. The Remain campaign was so passionate in making their case that they made voters suspicious.

That suspicion caused voters double down on their initial ‘gut feeling’ that it was time to leave.

#4 – It’s not about what you say.

There’s a theory in persuasion called cognitive response model. Simply put, it’s this idea that it’s not necessarily what a messenger says that carries the persuasive effect, it’s what the recipient says to themselves once they’ve heard the message. So if you’re persuading too hard and it causes someone to resist, and start arguing against your point, you may have already lost. People in the Remain campaign may have tried so hard to be persuasive that it backfired. — Steve Martin

This is hands down the most important lesson of all.

When you’re trying to make an argument, you tend to focus on what you are going to say and how you are going to say it.

But you are not the one who needs convincing.

You should be thinking about how the recipient of your message is going to respond to what you have to say.

What might their objections be? How will they react to certain arguments? How can you get them to reconsider their position?

Your argument is only the beginning of the conversation. How the recipient responds to what you say is far more consequential.

Bottom line: Be persuasive, but not too persuasive.

The Leave campaign won because their message was simple and direct, it spoke to people’s immediate concerns, and it reinforced a worldview that’s growing in popularity (Donald Trump anyone?).

They didn’t try to force a message down people’s throats. They engineered a simple but effective message from the outset. And they let people draw their own conclusions.